Category: Uncategorized

Todd Archbold’s Speech highlighting the MHCH at Mental Health Day on the Hill – 2/20/2025

November 2024 Impact Report

The Star Thrower Video

MHCH is a secure portal that helps connect youth and families in psychiatric or behavioral health boarding situations, such as an emergency department, to safe and healing treatment. Users can connect with appropriate living and mental health treatment settings based on the unique needs of the patient. Join the community of professionals helping youth get the care they need and deserve. Become a Star Thrower today: mnpsychconsulthub.com

Community Impact Award

UMN CW360 MHCH

The Mental Health Collaboration Hub

Getting to Yes! Kirsten Anderson, Todd Archbold, LSW, MBA, Christine Chell, BSW, MBA, Shelley Shea, RN, BSN

We have been living amidst an ongoing mental health crisis that has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The disruption to our daily lives and the various forms of trauma experienced across the globe has been recognized as a longer-lasting impact to our mental health. Every day in Minnesota dozens of youth present to hospitals and emergency departments in a psychiatric or behavioral health crisis. The number of youths in emergency departments in crisis has doubled in the last decade, overwhelming hospital staff and infrastructure that is designed for medical emergencies. Stories of youth boarded (stuck) on medical units, hallways, and even parking garages have become more common as they have no place to go. The situations are intense, and services are scarce. The time spent boarding is increasing as well, in some cases up to weeks or even months. This is a result of an underfunded and understaffed system of mental health care providers and human service systems.

In response to this crisis, in August 2022 stakeholders across the state began to meet to talk about the problem. Led by the Metro Health Coalition and AspireMN, they represented the state’s largest hospitals, counties, mental health treatment centers, group homes, and advocacy groups. Together, these previously relatively disconnected groups began identifying specific cases of youth who were boarding in inappropriate settings and trying to connect them to care. Most cases were boarding in hospitals and emergency departments, but some were boarding in county administration buildings and even hotels. The cases being discussed were among the most difficult to place. Many youths were in foster care or county custody, often lacking clear contacts for health care decision-making or coverage for services.

The provider group began meeting weekly and tracking their efforts in a secure SharePoint site. It became clear that there were paths forward, but it would require aligned goals, creativity, and tenacity to break through barriers. They dubbed their efforts, “Getting to Yes!” As each week passed, one or two kids were often able to get the necessary intervention and safe placement they needed. However, the efforts involved were extraordinary in the number of providers it took brainstorming options, and the process lacked efficiency.

The Minnesota Department of Health awarded PrairieCare, the state’s largest psychiatric health system, a Pediatric Mental Health Access Program grant through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). This funding allowed the provider group to build a secure online platform for centralized communication and automation. Thus, the Mental Health Collaboration Hub was born. The grant also helps to support administrative and technical support for the platform, as well as education and outreach. Any health provider or human services agency in the state can register their organization and build a profile to interact within the Hub. There are currently 170 organizations registered and nearly 400 individual users.

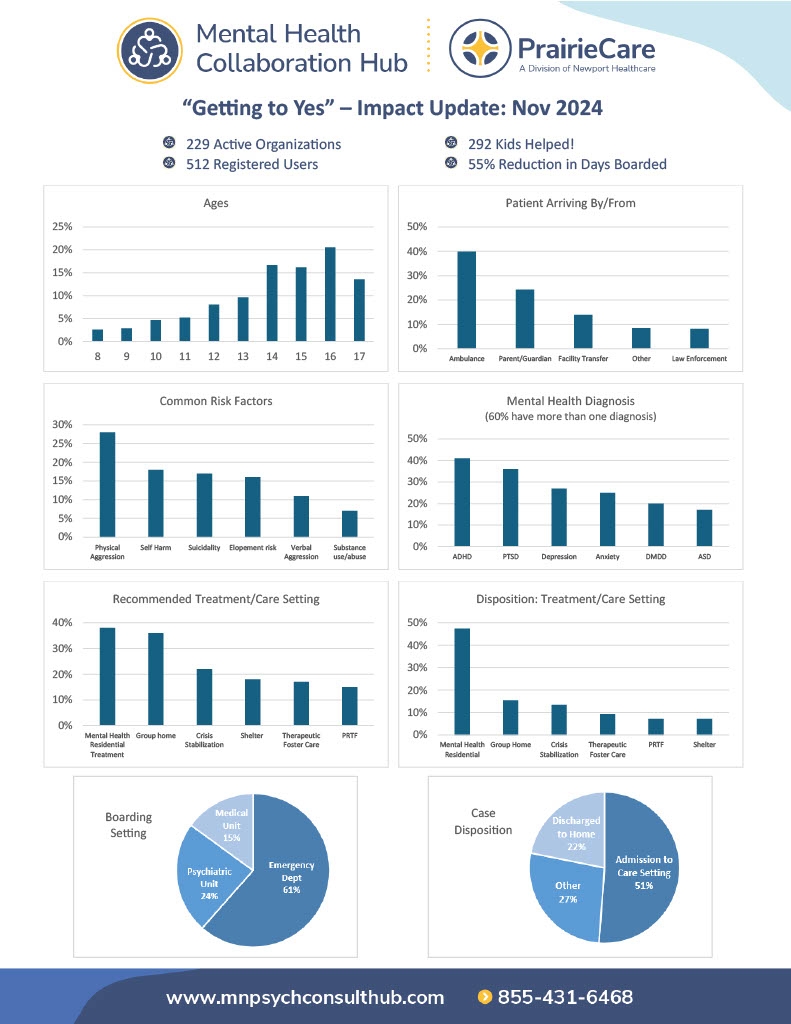

More than 200 cases were entered into the system within the first year, and aggregated data along with user interactions provide insights in a custom dashboard, available to all users. This includes a breakdown of ages, genders, diagnosis, risk factors, and more. While most youth who are boarding are struggling with a severe mental illness, it is most often the behaviors corresponding to those illnesses that are impacting their situation. Nearly 75% of all cases had two or more psychiatric diagnosis. The most common psychiatric diagnosis was PTSD or trauma related disorders (36%), followed by ADHD (31%), and then anxiety (27%) and depression (27%). There was also 17% of the youth who were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, which is a developmental disorder that may present through dysregulated behaviors.

Almost all boarding cases presented with additional risk factors, most often characterized as aggression, self-harm, suicidality, elopement risk, or substance use. It is often these behaviors that present risks to an intervention or safe placement. Many children on the hub with some of the most complex circumstances are in foster care and have a long history of not accessing needed care, with significant numbers of treatment stays, foster homes, and experiences of trauma.

The most sought-after treatment recommendation or placement was a group home (40%) followed by a residential treatment program (31%). Some youth have been able to benefit from a shorter-term intensive intervention such as psychiatric hospitalization, but most need longer-term ongoing stabilization in a safe setting, which may even include therapeutic foster care (20%). It is important for providers to understand the differences in care settings and how each of them can be accessed. Barriers to access often include lack of capacity in that setting (amplified by staffing shortages) or a lack of insurance coverage or county payment. Both barriers have made access to Minnesota’s crucial Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities (PRTFs) especially difficult.

Most children in boarding situations require complex mental health treatment provided by very specific levels of care that include group homes, children’s residential facilities (CRF), or psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTF). For individuals with a mental or behavioral disorder, it is critical to have a clear diagnosis, and only then can you understand the best treatment or intervention. The Diagnostic and Statistical manual of Mental Diseases (DSM) details more than 300 distinct mental illnesses in five general categories. The most common category of disorder that appears in the most complex boarding cases are neurodevelopmental disorders and externalizing disorders. For those with severe illnesses or behavioral conditions who require a long-term placement (i.e., residential treatment, group home or hospitalization), every bed type is different, serving a different population.

We now have a better understanding of the complexity of factors that lead to boarding situations based on the insights captured within the Mental Health Collaboration Hub. We know that the social determinants of health play a consistent role, as do social supports, and biological factors. The Mental Health Collaboration Hub has brought together a community of providers with shared goals and now a better understanding of what our communities need to prevent boarding situations. One clear achievement has been building relationships outside of the service silos that our professionals tend to operate within. We have acknowledged that a team approach is necessary to design services that meet the unique needs of each child – with counties, child welfare professionals, disability providers, and other community partners collaborating in “Getting to Yes”. However, we still lack the resources and services that our youth and families need. We also need to develop shared nomenclature and systems that result in better assessment and triage of youth with mental illness and behavioral conditions.

The Mental Health Collaboration Hub is a transformational tool that has opened doors, both figuratively and literally. However, it is merely a conduit to existing services – it has not created additional capacity, or improved funding for the services themselves. The result is a better connected, yet fraught system of mental health care providers and partners – including county and child welfare service providers – as we all strive to support youth in accessing the best treatment and service settings. We have discovered vulnerabilities and opportunities, and providers are constantly pivoting to remain viable.

Getting to Yes!

The MHCH has helped over 200 youth in behavioral health boarding situations get connected to mental health treatment providers and safe support in the community. Cases are submitted with de-identified information that matches to providers across the state who offer services that may help

Lessons Learned

In August 2022, hospital systems and child and family service providers started a grassroots effort to share ideas and resources to get to yes and deliver appropriate community-based care for children boarding in hospitals.

Designed to capture data and track outcomes, this effort has yielded valuable data and become a venue to identify barriers to care. The Mental Health Collaboration Hub is focused on children who are boarding and do not meet criteria for a hospital level of care. The model replicated the centralized communication strategy used during the COVID-19 pandemic which was supported by the coordination and leadership Metro Health Care Coalition.

- The collaboration launched with the consensus that it was better to attempt to coordinate resources to serve children who are boarding than to do nothing.

- Children are boarding in Juvenile Detention and “hoteling” with counties in addition to boarding in hospitals, the Hub has invited these systems to also engage and have had limited success in fully expanding to meet these unique system needs.

- Relationships are critical to Getting to Yes – within the MHCH and for designing solutions for children.

- Creating shared understanding of systems and networking is foundational to individualizing services for children.

- Clinical decisionmakers are essential to better understand the unique assets and challenges to provide individualized care.

- Transparency and candor are key features – to the extent it can be achieved with client and systemic limitations.

- Foster care is important and underrecognized as a critical factor to support children to access care in the community

- All systems players are required to design “yes” solutions (community providers, safety net providers, counties, state, and client/family/natural supports).

- Individualization is critical and challenging to achieve – due to barriers of information, timing, training and capacity to design individualized responses in an environment of scarcity.

- Liability concerns for both the boarding setting, and possible treatment setting are added barriers.

- The ability to support a child with unsafe behaviors is challenged by: staffing (ability to staff 1:1), training (equipping staff to best support the child), milieu safety concerns, insufficient information shared with the service providers.

- Care needs often fall within numerous disconnected service silos, requiring bespoke coordination for optimal intervention.

- Families are often not able to fully engage; they have been challenged with the lack of care and are reluctant to trust, often mired in their own life challenges, and other complexities can make full participation difficult or impossible.

- We need greater flexibility in residential care – especially group home level of care where services can be individualized and where children are able to experience stability.

- Counties authorizing payment for care in a timely manner is a common barrier.

Looking Forward

- The Mental Health Collaboration Hub will continue to gather data and perspective that is otherwise not available in our system; including learning from care pathways that come from discussions and collaborative work.

- Leverage growing dataset to create shared understanding between providers and policymakers.

- Identifying resources to support creative service solutions and expedite care when there are delays for the payor is an opportunity to improve outcomes and pilot solutions that may have greater systemic application.

- Collaborate with the newly stood-up Acute Care Transitions team within DHS to swiftly identify and execute the systemic flexibilities and enhanced funding required to get to yes for children boarding.

A bed is not a bed

There is an alarming number of youths in psychiatric or behavioral health crisis stuck boarding in emergency departments, medical units, county buildings, jails, and even hospital parking garages. These situations are intense, and the needed interventions and services are scarce. The average time spent boarding is increasing, in some cases up to weeks or even months. This is a result of an underfunded and understaffed mental health care system, that is ever-changing.

Complex mental health needs:

Most youth in boarding situations require complex mental health treatment provided by specific programs that range from group homes, children’s residential facilities (CRF), therapeutic foster care psychiatric hospitals, or psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTF). The American Psychiatric Association has defined nearly 10 different types of inpatient psychiatric beds. While not necessarily standardized, they range from state operated and community-based to specialized geriatric and forensic. For individuals with a mental or behavioral disorder, it is critical to have a clear diagnosis to understand the best treatment or intervention. The Diagnostic and Statistical manual of Mental Diseases (DSM) details more than 300 distinct conditions. The most common disorders in boarding cases are neurodevelopmental and externalizing disorders characterized by aggression, opposition, and maladaptive behaviors. Nearly 75% of these cases have multiple diagnosis that often include autism, developmental delays, ADHD, conduct disorder, and substance abuse. This requires the boarding settings to manage risk factors such as self-harm, elopements, suicidality, and combativeness.

A shortage of facilities:

More than 80% of counties in Minnesota have a shortage of mental health professionals. We have seen a 30% reduction of children’s residential treatment beds since 2020, and there are fewer than 200 operational inpatient psychiatric beds for youth in the state today. This is a startling lack of options that is further exacerbated by staffing shortages that limit these capacities. Minnesota currently has 93 licensed children’s residential facilities with a total of 1,586 beds, each serving a unique population. Facility sizes range from a handful of beds to large campuses with upward of 100 beds. Each facility serves a distinct age range, specializes in treating certain conditions, and may have acceptance criteria regarding gender, IQ, and county of residence. Additionally, certain certifications are required to treat conditions such as substance use disorders. Some specialties include eating disorders, autism, sexual misconduct, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. It is not uncommon for organizations to change acceptance criteria as they evolve, particularly the age range that they treat. These various specialties can be highly effective for some individuals, but the imbalance of capacity within each of them and the constantly changing landscape creates frustration for providers making referrals. Creating a shared understanding of the nuances in the different types of beds will strengthen our ability to collaborate and help kids.

Mental Health Collaboration Hub

Mental Health Collaboration Hub